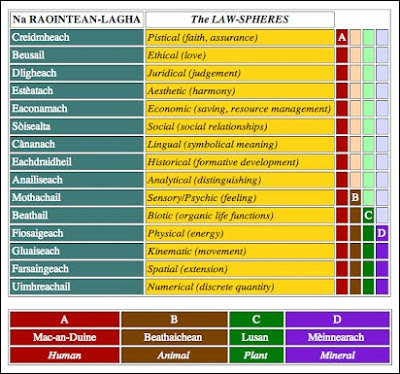

THE 15 IRREDUCIBLE LAW-SPHERES

OF OUR EXPERIENTIAL HORIZON

Also called Aspects/ Modes/ Modalities/ Meaning-sides

(Diagrams by FMF)

NOTES (FMF):

No law-sphere (aspect) can be reduced to another. Infringements of 'irreducibility' are behind all 'isms'. These 'idolatries' show the human heart attempting to integrate entire reality around a single aspect (or 'law-sphere'). There is a plausibility to this because each aspect is present as an analogy in every other aspect (see 'Historical Aspect' diagram below). This gives each aspect an omnipresence, which Dooyeweerd designates 'sphere-universality'. Crucially, since no aspect can be reduced to another, none can be reduced even to the 'Logical / Analytical Aspect' (in other words, the above panoply of aspects is not a theoretical product of "logic" - it is "experiential", it is "intuitive consciousness"). This must be particularly and continually emphasised. Failure to bear that specific fact in mind makes a 'logicism' out of Dooyeweerd's philosophy, when it is primarily against logicism that he is arguing (Dooyeweerd's 'A New Critique of Theoretical Thought' is essentially a critique of Kant). A moment's reflection will observe that the aspects correspond pretty closely to standard academic disciplines.

It is key to Dooyeweerd to appreciate his insistence that there is no thinking without a thinker ("the hidden performer on the instrument of philosophic thought" (Prolegomena, New Critique). The thinker ALWAYS functions in ALL aspects, but transcends them all in the concentration-point of his or her deepest selfhood ('heart'), which is directed towards or away from the Living God Who alone gives meaning to temporal reality. In refusing God as only source of meaning, a substitute ultimate focus is sought by the selfhood within the temporal cosmos by absolutising a law-sphere (or combination of law-spheres). Hence the idol.

Dooyeweerd calls the irreducibility feature of each aspect 'sphere-sovereignty'. With reference to mutual irreducibility, Dooyeweerd draws attention to Genesis 1 where animals are created "according to their kinds". Without getting a handle on the terms 'sphere-sovereignty' and 'sphere-universality' it will be impossible to fathom Dooyeweerd's explanations on just about anything!

Interestingly, the absolutization of any given aspect of reality invariably throws up its 'counter-idol', leading to a dualism. Something like an after-image. The counter-absolute arises as the 'Economic Aspect' of reality resists unbridled profligacy in one direction, the 'Aesthetic Aspect' resists the consequent disharmony, the 'Juridical Aspect' (eventually) avenges the destructive bias via a swing towards the counter-polarity.

Examples:

Rationalism 'deifies' the 'Logical/ Analytical Aspect'. It infringes the irreducibility of the other fourteen aspects by attempting to reduce them all to the 'Logical/ Analytical Aspect'. That is, Rationalism implies that every other aspect is a product of the absolutized 'Logical/ Analytical Aspect' (cf Kant).

Philosophical Materialism 'deifies' the 'Physical/ Energy Aspect'. It infringes the irreducibility of the other fourteen aspects by attempting to reduce them all to 'matter', ie to the 'Physical/ Energy Aspect'. That is, Philosophical Materialism implies that every other aspect is a product of the absolutized 'Physical/ Energy Aspect'.

Combinations of the above have provoked the prevailing (humanist) 'Nature/ Freedom' dichotomy, ie that between 'Absolute Mathematical (or Natural-mechanistic) Law' and 'Absolute Personal Freedom'. The irreconcilable conflicts of this dualism are perenially revisited in movies and TV series such as the Terminator, the Matrix, Battlestar Galactica, etc.

Postmodernism is another irrationalist (subjectivist) reaction to the 'rationalism' of reducing reality to 'One Big Story' dogmatically layed down by autonomous human thought. Many films now interrogate reality from a postmodern viewpoint, eg 'Inception', 'Sourcecode', various Tarantino movies, etc.

Christians often labour under their own 'Nature/Grace' dualisms which lead for example to a gnostic or pietistic flight from the world.

-------------

"It is an undeniable fact that in the first life-phase of a suckling baby feeling precedes the first development of logical distinction; the latter precedes the controlling manner of forming sounds, which in turn precedes the primitive symbolical designation of concepts by words etc. But that does not prove that the higher mental functions originate from feeling as their undifferentiated origin. Rather it testifies to the truth of our view of the order of the modal aspects of experience, as a real temporal order, related to subjective duration in the genetic process." (Herman Dooyeweerd, A New Critique of Theoretical Thought Vol II pp 112,113)

__________________________________________

The above diagram focuses on the 'Historical/Culturally Formative Aspect'. Besides its own irreducible (supratemporal) nucleus, its structure includes anticipatory (here in green) or retrocipatory (blue) analogical moments dynamically relating to the other fourteen aspects. The weighting of blues to greens in any given aspect depends on where that aspect appears in the fixed temporal order (compare colour sequence in a rainbow).

Thus (now considering all aspects, not just the Historical), in our everyday lives a 'feeling of claustrophobia' might be analysed as a 'Spatial' retrocipation within the 'Sensory (or Psychical) Aspect'. A 'prolix speech' as an 'Economic' anticipation within the 'Lingual Aspect'. An 'elegant stumble' would be an 'Aesthetic' anticipation within the 'Movement/Kinetic Aspect'. A 'vital clue' a 'Biotic' retrocipation within the 'Logical/Analytical Aspect'. And so on.

It should always be borne in mind that, however inadequate the above diagram, what is being referred to is the fabric of actual cosmic reality within which all aspects structurally combine, as spectrum colours combine to form clear daylight.

Dooyeweerd sees the Divine call of civilization as a historical “opening-process”. Each succeeding aspect is "unfolded” in response to the light of God. Reactionary societies attempt to close down such burgeoning differentiation.

EVERY human ACT in thought or deed

ALWAYS involves ALL aspects.

"Keep your heart with all diligence,

for out of it are the issues of life."

(Prov 4:23)

________________________________________

VOLUME II, CHAPTER IV

§ 1 - THE UNIVERSALITY OF THE MODAL ASPECTS WITHIN THEIR OWN SPHERES

The sphere-sovereignty of the modal aspects of reality has its counterpart in the universality of each aspect within its own sphere.

The term 'sphere-universality' is intended to signify that the modal meaning-structure in each aspect gives expression to the entire coherence of meaning of all the law-spheres.

This is made possible by the retrocipations and anticipations in each meaning-modus. Immanence philosophy could not help misinterpreting this state of affairs, because of its failure to grasp this universality in relation to the modal sphere-sovereignty.

Why the different attempts at absolutizing seem to be acceptable.

The universality of each modal aspect within its own sphere may also explain the apparent success of the various absolutizations in immanence philosophy.

Hume's 'Sensory / Psychical Aspect' reductionism.

DAVID HUME, e.g., resolves the whole of given reality in impressions of feeling, or 'perceptions'. He calls out: 'Let us chase our imagination to the heavens, or to the utmost limits of the universe; we never... can conceive any kind of existence, but those perceptions... This is the universe of the imagination' (A Treatise of Human Nature I, Part II, Sect. VI. Italics are mine). In this exclamation we distinctly hear his conviction that he has discovered an undeniable state of affairs.

DAVID HUME, e.g., resolves the whole of given reality in impressions of feeling, or 'perceptions'. He calls out: 'Let us chase our imagination to the heavens, or to the utmost limits of the universe; we never... can conceive any kind of existence, but those perceptions... This is the universe of the imagination' (A Treatise of Human Nature I, Part II, Sect. VI. Italics are mine). In this exclamation we distinctly hear his conviction that he has discovered an undeniable state of affairs.

And indeed, whatever the critical transcendental philosophy might have to say against HUME, the thesis that in 'feeling' the universe expresses itself in the whole of the cosmic meaning-coherence is irrefutable. The analysis of the meaning-structure of the law-sphere of feeling in the retrocipatory and in the anticipatory direction of time confirms the universality of this meaning-modus in every respect.

This structural analysis of the psychical modality does full justice to the kernel of truth in HUME's psychologistic conception. At the same time it lays bare the fundamental error of his psychologistic absolutization, whereas the Kantian epistemological criticism touches the root of this absolutization so little that it becomes itself guilty of absolutizing the transcendental-logical structure of thought.

The universality of the modal meaning of feeling implies that the psychical law-sphere is not self-sufficient. This universality is only possible as a modal universality of the aspect within its own sphere. Its absolutization is equal to its theoretical cancellation.

Therefore, HUME's epistemological psychologism destroys itself if it is consistently thought out. The epistemological thesis that the whole universe is given us only in psychic 'perceptions' cannot be correct. For nothing is given in theoretical abstraction.

The modal meaning of feeling itself cannot be given "an sich" (in itself), i.e. apart from the cosmic meaning-coherence in which it can function only as psychical modus.

Psychologism may try to escape from the force of this argument by answering that here we are exclusively concerned with the problem whether or not we can be aware of anything outside our impressions of feeling. But the opinion that we are at least only conscious of our psychical perceptions, is equal to the denial of any possibility of being conscious of anything. This view results in a radical kind of epistemological nihilism. Being conscious of one's impressions of feeling implies the self-consciousness of the whole of the cosmic meaning-coherence. In this coherence, feeling only exists as a modal meaning-function that lacks self-sufficiency.

Kant's 'Logical / Analytical Aspect' reductionism.

The appeal to a supposed absolute subjective pole of thought in the transcendental cogito cannot hit the heart of psychologism. In the Prolegomena we have disclosed the speculative trap in the conception of the self-sufficiency of the transcendental-logical function of thought. At bottom this self-sufficiency is open to the same criticism as the psychologistic view. A genuinely transcendental epistemological criticism necessarily reveals the self-insufficiency of the transcendental-logical function of thinking, both in theoretical self-reflection and with regard to the temporal intermodal coherence between the experiential aspects. This coherence only makes transcendental logical thought possible. [Or perhaps better: 'Only this coherence makes transcendental logical thought possible.' ?? FMF]

The appeal to a supposed absolute subjective pole of thought in the transcendental cogito cannot hit the heart of psychologism. In the Prolegomena we have disclosed the speculative trap in the conception of the self-sufficiency of the transcendental-logical function of thought. At bottom this self-sufficiency is open to the same criticism as the psychologistic view. A genuinely transcendental epistemological criticism necessarily reveals the self-insufficiency of the transcendental-logical function of thinking, both in theoretical self-reflection and with regard to the temporal intermodal coherence between the experiential aspects. This coherence only makes transcendental logical thought possible. [Or perhaps better: 'Only this coherence makes transcendental logical thought possible.' ?? FMF]

The really radical criticism of the conception of the "Unbedingtheit" (absoluteness, unlimitedness, being unconditioned) of transcendental logical thought is the analysis of the structure of its universality of meaning within its own sphere. Such an analysis also explains the seeming plausibility of the transcendental-logicistic conception. But more about this later on.

In the same way we can show the fundamental error of historicism, aestheticism, mathematicism, biologism, etc., viz. by a structural analysis of the universality of each of the law-spheres absolutized by them.

The Divine irony in the history of apostate philosophy.

The universality of each of the law-spheres within its own boundaries can only be seen in its true structure from the Christian transcendence-standpoint.

Immanence-philosophy continually goes astray, because in its Archimedean point lurks a primary absolutization of meaning.This absolutization is due to a misinterpretation of the universality of each law-sphere within its own limits. There is a Divine irony in the development of apostate philosophy, since the temporal world-order at first seems to justify every kind of theoretical absolutization in an equal measure. When viewed from the immanence-standpoint, is not historicism as convincing as a logicistic or a psychologistical interpretation of empirical reality? Is not it an indisputable fact that in theoretical thought as well as in the life of human feeling is revealed the prevailing tendency of a special period of history? Is it not true that HUME's psychologism as well as KANT's transcendental philosophy bear the stamp of modern western culture?

HUME asserts that the universe is given to us only in psychical impressions. Wherever we direct our gaze we are supposed to find nothing but 'perceptions'. But cannot this music be transposed with equal justice into the key of the historical aspect?

HUME thinks he can start from some permanent uniformity of human nature. He places his epistemology outside the current of historical development. Is this not a false dogmatism when confronted with the indisputable universality of the course of historical development?

Indeed, historicism cannot be dethroned solely with formally-logical arguments, no more than transcendental psychologism will capitulate to a logicistical transcendental philosophy.

Only the insight into the universality of the historical aspect within its own sphere reveals the fundamental error of historicism and the grounds for its seeming plausibility.

The cosmic order passes an internal judgment on the theoretical absolutizations of immanence-philosophy, which invariably result in internal antinomies. We cannot interpret the Divine order on the basis of a self-sufficient and autonomous reason. Apart from the Divine Word-revelation, this order maintains the unfathomable silence of the Sphinx.

So long as pistis (faith) remains closed to this Word-revelation, theoretical thought remains under the ban of mythology. The Divine world-order begins to appeal to us only when our heart and our function of faith are open to the voice of God's Word. Then we become aware of the religious foundation of that wonderful universality of each of the modal aspects. For only in the disclosed insight into this profound state of affairs does the Christian see the true connection between temporal reality and the Christian religion in the theoretical cognitive attitude. In the pre-theoretic attitude of thought s/he ought to experience this relation immediately in faith apart from any theory.

Anyone who, as a Christian thinker, has seen through the modal sphere-universality, cannot fall back into the nominalistic dualism between believing and thinking, and between 'nature' and 'grace'. Every dualism of this kind makes the temporal modal functions self-sufficient with regard to their religious root. But there is nothing in time that can be set apart and by itself.

Anyone who, as a Christian thinker, has seen through the modal sphere-universality, cannot fall back into the nominalistic dualism between believing and thinking, and between 'nature' and 'grace'. Every dualism of this kind makes the temporal modal functions self-sufficient with regard to their religious root. But there is nothing in time that can be set apart and by itself.

The Idea of the universality of each aspect within its own sphere should be related to the process of disclosure in the temporal cosmic meaning-coherence in order to reveal its full import.

The new problem: The intermodal disharmony in the opening-process.

But at this very point Christian philosophy is once again confronted with the problem concerning the influence of sin on this process. If it were permissible for a Christian to choose a purely eschatological standpoint with regard to our sinful cosmos, the Idea of universal meaning-disclosure would no longer hide any internal tensions and antitheses.

The Idea of the fulfilment of meaning in Christ undoubtedly implies that in the specific universality of each law-sphere the opening-process gives temporal expression to the full religious abundance of God's creation both on its law- and its subject-side.

In this world, however, this sphere-universality cannot unfold itself perfectly in accordance with the guidance of the religious fulness of meaning. The development is affected by sin, otherwise the refraction of the fulness of meaning in time would no-where be experienced as disharmony. If there were no sin, the harmony among the law-spheres would be fully realized, just as in a perfect work of art. In such a work the 'natural' sides of the material are subjected to the guidance of the aesthetic structural function to such a degree that they no longer obtrude themselves as a disconcerting resistance. In their individual deepening of meaning and 'spiritualization', they are a pure expression of the artist's conception. Reality is, alas, different. The deification of the temporal meaning-aspects of the cosmos in apostate faith, expanded to free striving leadership, causes a fundamental disharmony in the opening-process.

In the previous chapter this disharmony was only considered in its modal historical sense. But we have now to examine it in the intermodal coherence of the different aspects of the process of meaning-disclosure.

If apostate faith gains the functional guidance in the opening-process, the subjection of the latter to the Divine world-order is not thereby cancelled. The Creator of Heaven and Earth maintains the functional-structural law-conformity in the disclosure of the temporal modal aspects against any human arbitrariness. If the Divine order in the temporal cosmos were not kept intact and elevated above any kind of human hubris, the manifestation of sin in time would not even be possible. For the whole of temporal reality would then burst like a soap-bubble.

Does this mean that the effect of sin leaves the law-side of the creation entirely unaffected, and can only manifest itself on the side of the subject?

But such a view would be at variance with the structure of the cosmic order analysed in an earlier part of this work. For in all the normative law-spheres the nómos (law) has been laid down only in the form of a principle. These Divine 'principia' have been left to human formation and positivizing in accordance with the modal structure of the law-spheres.

In the opening-process of the normative anticipatory spheres even the laws of the pre-logical aspects require this human intervention for their deepening of meaning. From the point of view of the structure of the temporal cosmos we can state that the disharmony in consequence of sin must necessarily also manifest itself on the law-side in the work of human formation and positivizing.

In this human interference the Divine structural principles are doubtless maintained and saved from human arbitrariness. Even the most impious law-maker or former of history can only form law or culture by the formation and positivizing of super-arbitrary principles founded in the order of creation (These principles are to be sharply distinguished from the subjective principles of political parties).

The formal abolishing of paternal authority by the first wave of the French Revolution was one of the many 'paper decrees' which, as an expression of human hubris, were swept away by what is very inadequately termed the logic of the facts. By setting aside the normative principles of law, morality, or culture, human arbitrariness can create a social chaos; it cannot create juridical, moral or historical norms in this way.

The human work of formation remains unshakably bound to the Divine structural principles of the normative law-spheres. But in this very work of formation and positivization the process of opening of the temporal meaning on the law-side cannot be carried out harmoniously, when in apostasy it has lost its direction to the religious fulness of meaning. Disharmony on the law-side is then inevitable, because the opening-process invariably moves in the direction of the absolutizing of certain meaning-moments.

It would be an illusion to think that this disharmony would not appear if the work of formation and positivization were only in the hands of Christians. For on the one hand, a Christian remains a thoroughly sinful creature, no better in himself than others. And on the other hand, the Christian former is bound to the history of mankind as a whole. In keeping with the entire structure of the Divine world-order, he cannot escape his historical position in a society in which the power of the civitas terrena ['Godless city' FMF] is clearly revealed.

Within the opening-process of temporal meaning the position of genuine Christianity is one of restless struggle. In its temporary defeats and victories Christianity bears witness to the sinful broken state of its existence and that of the entire earthly creation; its position is only justified through faith in Christ. In Him the struggle for historical power in the opening-process may become a temporal blessing for a corrupted and broken world. The Christian Idea of the opening-process, guided by the faith in Christ as the Redeemer, cannot detach itself from sinful reality in an idealistic optimism. This Idea would then become false and worthless to temporal life. It must rather remain broken in character, in spite of its direction to the Root of reborn humanity, to Christ Jesus and to the Sovereign Creator, Who is willing to be our Father in Him.

Only in its eschatological expectation of the ultimate full revelation of the Kingdom of God can Christian belief rise above this broken state without losing its relation to the sinful cosmos. For the same reason the Idea of the universality of each of the aspects within its own sphere cannot be conceived in a purely eschatological sense; it should also be related to our sinful cosmos.

This Idea retains its normative transcendental direction to the consummation of meaning in Christ. But at the same time it should give us an insight into the disharmony that the process of disclosure shows in apostasy. Only in this way can we arrive at a satisfying conception of the Christian Idea of cultural development.

Attention should first be directed to the disharmony in the opening of meaning on the law-side of the normative aspects due to apostate faith. This theme can only be treated in an exemplifying way. Our examination will restrict itself to an analysis of the influence of faith in the mathematical Humanistic science-ideal upon the opening-process in the different spheres. It stands to reason that this influence could not fail primarily to reveal itself in the domain of science.

[----]

§ 4 - FINAL REMARKS ON THE CHRISTIAN IDEA OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT.

To Humanistic philosophic thought the disharmony, manifesting itself even on the law-side of the opening-process in the sinful cosmos, changes into antinomy. This is the original antinomy in the two basic factors of the Humanistic cosmonomic Idea: the ideal of science and that of personality.

For the Christian philosophic consciousness, however, conforming to the fundamental structure of the Christian cosmonomic Idea, without compromising with immanence-philosophy, it is impossible to accept antinomies in the Divine world order, even in this sinful world.

The disharmony referred to manifests itself only as a defect in the opening-process under the curse of sin. For a Christian there can be no question of the inner antinomy that Humanism has to experience on seeing how human personality, claiming to be autonomous in its self-sufficient freedom, is being enslaved by its own rational creations. The Divine world-order is not itself antinomic when it avenges itself on every deification of temporal meaning by the disharmony caused on account of this apostasy in the opening process. No more is it antinomic when it causes philosophical thought to entangle itself in inner antinomies, as soon as this thought supposes it can ignore the Divine order.

This world-order binds the normative process of disclosure, in the foundational direction of time, to the historical formation of power. In the transcendental direction it binds the opening-process to the direction of faith, and at the same time the world-order points beyond and above all the temporal law-spheres to the religious radical unity of the Divine law. That is why truly Christian philosophic thought cannot discover any antinomy nor any paradox in the validity within a sinful world of the full religious demand of the Divine law. This law even remains in force in a world in which the temporal ordinances of the law-spheres through sinful human formation have been drawn away from their direction to the fulness of meaning of the Divine law.

Holy and without any inner contradiction is the world-order, even when it binds the possibility of a defective positivizing of Christian principles to a historical basis of power and to the guidance of true Christian faith.

Holy and without inner contradiction is the world-order, when it avenges itself on the process of disclosure in which the civitas terrena ['Godless city' FMF] has gained the power to direct the formation of history.

The defectiveness caused by sin in the root and the temporal refraction of meaning, has been expressed in our transcendental basic Idea itself in the struggle between the civitas Dei ['Godly city' FMF] and the civitas terrena ['Godless city' FMF]. It must therefore also naturally find its expression in our Idea of historical development, in our economic Idea, in our Idea of justice, of morals, of beauty, etc.

The Christian Idea of cultural development cannot be guided by an optimistic faith in the steady progress of civilization. It cannot be sacrificed to pessimistic relativistic Historicism either. It remains ruled by the religious basic motive of the struggle between the civitas Dei ['Godly city' FMF] and the civitas terrena ['Godless city' FMF] in the temporal course of history, though eschatologically it remains directed to the ultimate victory of the Kingdom of God in Christ, to Whom has been given the fulness of power in the religious fulfilment of history.

The methodical application of the Christian Idea of cultural development in historical science.

The functional structure of the opening-process, in connection with the modal universality of the aspects, each in its own sphere, provides us with the insight into the only possible method of using this Idea of development in historical investigations.

Our analysis has yielded a univocal criterion to distinguish between primitive and disclosed cultural spheres, which criterion is a necessary hypothesis for historical science proper. We saw further that a real opening of the historical aspect is possible under the guidance of an apostate faith, and that in this case the process of disclosure must show its disharmonious character also on the law-side of the aspects. We have frankly to acknowledge that apostate movements have their special task in history when they have gained the power to form and to positivize deepened cultural principles of development.

But this entire view of history implies a radical rejection of Historicism. We have explained (cf. our analysis of the universality of the aspect of history in its own sphere) that any true meaning-disclosure of history points beyond and above this aspect and is only possible in the universal temporal meaning-coherence of all the modal law-spheres.

The Christian Idea of development, therefore, cannot be narrow-minded. It recognizes any relative meaning-disclosure of civilization, even though positivized by anti-Christian powers. Every spiritual movement, having the power of historical formation has to fulfil its own task as an instrument in the hand of God. Our developmental Idea has broken with any speculative philosophical or theological construction of periods in cultural development. And above all, it continues to observe the inner tension between sinful reality and the full demand of the Divine law.

This demand is terrifying when we consider how much the temporal ordinances labour under the destructive power of the fall into sin. Terrifying also, when it puts before us our task as Christians in the struggle for the power of cultural formation.

For it makes a demand on us which as sinful human beings we cannot satisfy in any way. And it urges us, in the misery of our hearts, to seek refuge with Christ, from Whose fulness, nevertheless, a Christian can derive the confidence of faith to carry on the ceaseless struggle for the control of cultural development. This is the remarkable 'nevertheless' of Christian faith.

Christian philosophic thought has to fight shy of self-exaltation, because it is directed in its root to Christ. The whole struggle that positive Christianity has to carry on for the direction of the opening process is not directed against our fellow humans, in whose sin we partake and whose guilt is ours and whom we should love as our neighbours. That struggle is directed against the spirit of darkness who dragged us all down with him in the apostasy from God, and who can only be resisted in the power of Christ.

As Christians we shall hate that spirit because of the love of God's creation in Christ Jesus.

(Herman Dooyeweerd: 'A New Critique of Theoretical Thought', Vol II, pp 331-337, 362-365)

Full text of above book can be freely read online, or downloaded as pdfs HERE.

(Herman Dooyeweerd: 'A New Critique of Theoretical Thought', Vol II, pp 331-337, 362-365)

Full text of above book can be freely read online, or downloaded as pdfs HERE.

A recent four-volume hardback facsimile reprint is also available (Paideia Press).

______________________